Today and tomorrow my schedule is super busy, so I’m sharing stories from Echizen-Wakasa Kidan for A-Yokai-A-Day again this weekend, as I don’t have any spare time to paint. Today I was busy filming video for a Kidan exhibition in Fukui City this November. In addition to an art gallery and story exhibit of many of my yokai paintings and the yokai in Echizen-Wakasa Kidan, there is also going to be a section produced by students from Fukui University of Technology, and I spent today working with students on their part of the exhibition. It reminded me of my days back in art school, and I’m really glad that these kids are getting the chance to produce a section of a major art exhibition. It’s a great opportunity for them.

Tonight’s story is one of the longer ones from the book, and it has a much more narrative telling than a lot of what we’ve seen so far this month. There are several amusing parts — first, the haughty young samurai coming in and thinking they are saving the villagers, only to make things worse; then, the hero of the story somehow holding his breath for an inhuman amount of time. It smacks of tall tale all around, and I love it!

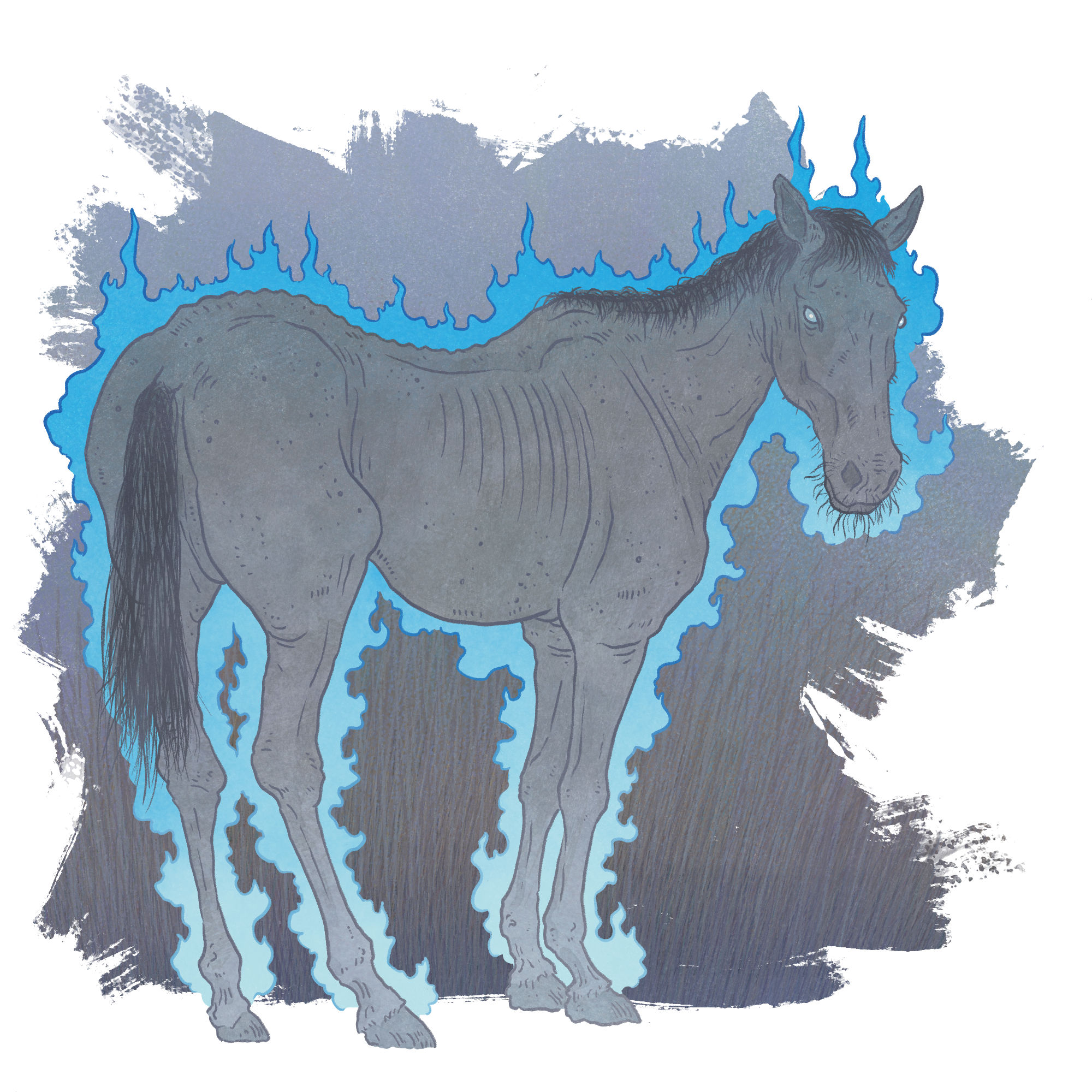

This one was particularly hard to paint, because the extremely vague description of the nushi of the lake. The word nushi means “master” and is used both for people, as in “master of the house,” or “let me speak to your master,” but it is also used for spiritual beings that are the lords of bodies of water, large rocks, mountains, and so on. It’s basically like a tutelary spirit, but it can take all kinds of forms — from dragons, to eels and catfish, to spiders, snakes, and so on. The nushi in this story sounds like something enormous… and Senzaemon manages to just chop a bit off of it. Like a buried kaiju or something. But from the description it is impossible to tell what it could be. What’s your best guess?

The Lord of the Lake

from Kaishū yakō no tama

In Echizen Province, about 5 kilometers from the castle town of Fukui, are the villages of Kakuzen and Futaomote. Between these two villages was a large pond. It was about 220 meters around and somewhat bleak, and in the center of the pond was an area about 90 centimeters wide of clear, blue water. Every year on March 3rd, both villages would prepare an offering of one koku of sekihan and cast them into the center of the pond. This was an old tradition, and they never neglected to perform it. If they failed to do it for even one year, the two villages’ rice fields, which normally yielded 3000 koku, would not produce even a single grain of rice.

One time, five or six young samurai from Fukui Domain went on an excursion and came to this area. One of the samurai said, “They say that a nushi has lived in this pond for a long time. Offering it sekihan every year becomes an expense for these two villages. Would it be so hard to go down into this pond, see if there’s anything suspicious down there, and kill it? I don’t care who does it, but there’s no reason someone who’s a good swimmer shouldn’t go down into the pond and check it out.”

Among the group was a samurai called Urakami Senzaemon, who upon hearing this said, “I’ve been thinking the same thing for some time. I will go and see what is going on.” After that, they all got onto a boat and went out to the center of the pond.

“First let’s measure the depth,” they said. They attached a stone to a rope and dropped it into the pond, lowering it deeper and deeper, but it never reached the bottom. After a while, when the stone had settled, they pulled it out and measured the depth at around 261 to 345 meters. “Perhaps the rope got twisted in the water,” they said, and tried again; but the depth was the same as the first time, not one bit different. Senzaemon said, “Well, I’ll go into the water and check it out.” Stripping off his clothes, he took his sword in hand, tied the rope to his loincloth, and said, “If there’s anything there, I’ll tug this rope. When that happens, you guys pull me up.” Then he dove into the water.

Some time later, the water in the pond turned scarlet and blood began to gush up. The people on the boat were surprised and said, “Senzaemon must have failed. Let’s go after him.” Three of them jumped into the water. About one hour later, Senzaemon and the three men who went in after him emerged from the water unharmed.

Senzaemon turned to the men on the boat and said, “At the bottom of this pond there is a spot about 1.8 meters wide covered in white pebbles. The water is indescribably pure and refreshing. There was something like a 60-centimeter long piece of scrap wood there and nothing else at all. Thinking there was nothing else strange down there, I tried to pick up the wood, but it was too heavy to lift. I tried cutting the piece of wood, and it bled profusely. And here is the scrap-wood-like thing.” The object he produced was hard like a turtle’s shell on top, and the bottom dangled like a jellyfish.

Everyone was puzzled, but thinking that there would be no more trouble, they called people from the two villages together and told them what had happened, and announced that it would no longer be necessary to put sekihan in the water anymore.

The following year, when the two villages didn’t put sekihan into the water, the crop failed just as it had in the beginning, and not a single grain of rice was harvested. So thereafter, every year they have offered one koku each of sekihan without fail, to this day.