This weekend I am in Kyoto for the KaiKai Yokai Festival and Mononoke Ichi yokai market. And while I would love to be able to paint these two days, this festival is super busy and there’s just no way to operate a booth as well as complete a painting. So I’m scheduling this weekend’s posts in advance just to make sure you are all supplied with yokai while I am away on business! I’ll also have photos to share of the festival after I get back, but for now please enjoy this preview of my upcoming book, Echizen-Wakasa Kidan!

(And if you haven’t checked it out yet, visit my Kickstarter for the book and check out what great rewards you can get if you back this project!)

This story comes from an 18th century book called Kimama no ki. The translation below is not the final version from the book; it is just a rough draft that will be refined before publication.

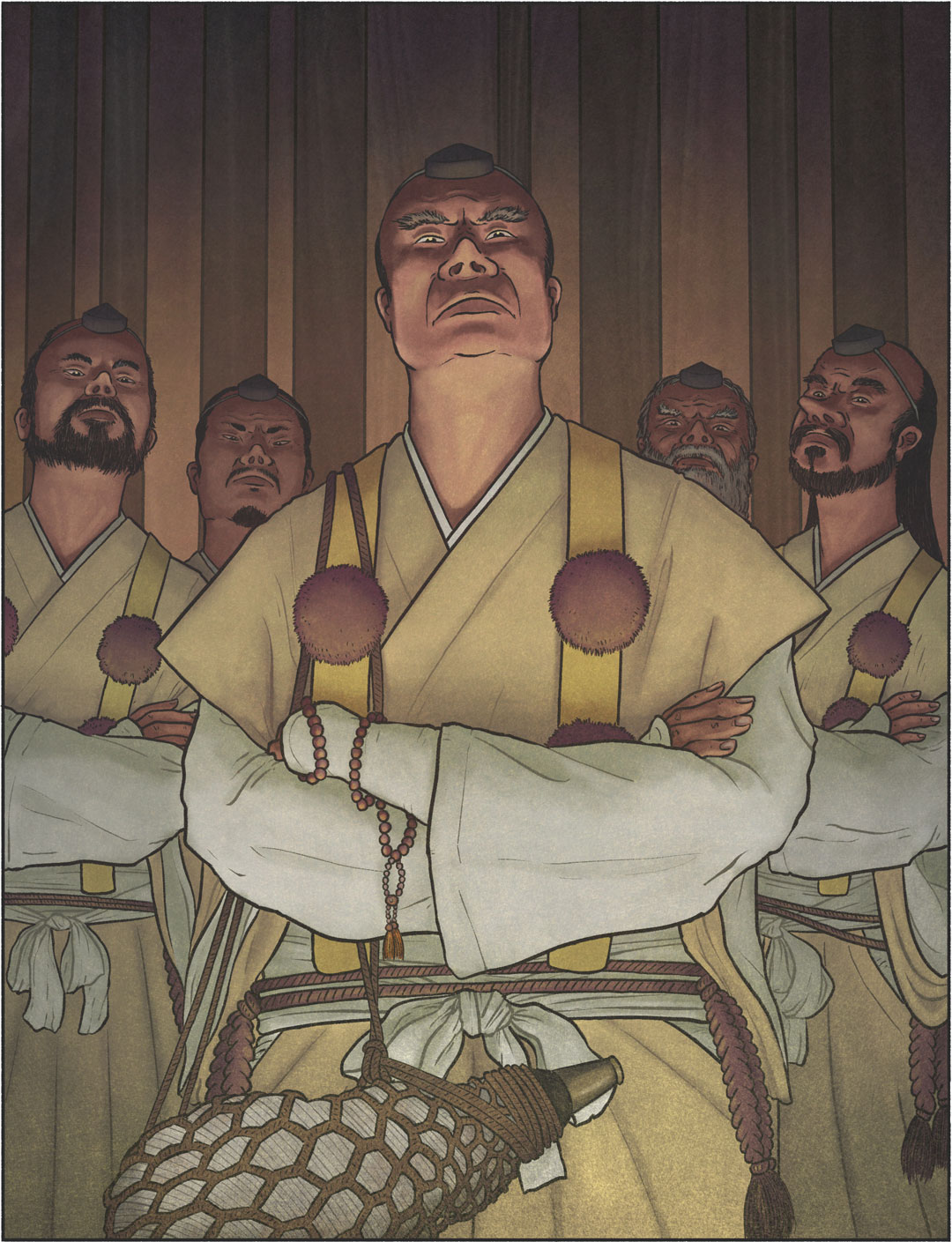

The Yamabushi of Takurayama

This took place in Keichō 8 (1603), during the construction of Echizen Kitanoshō Castle (later Fukui Castle). A large number of laborers went into Takurayama (in Minamiechizen-chō) to cut down timber for the castle’s main gate. Then, out of nowhere, five or six burly yamabushi came to manager Ogasawara Rihei’s cabin and asked for tea.Then they said to Ogasawara, “What is the reason for cutting down these trees? We know that the trees found here, so deep in the mountains, cannot be harvested just anywhere. We have made pilgrimages all over the country and we know all the history of the mountains and rivers. Why don’t you stop cutting down these trees?”

Ogasawara thought to himself, “Yamabushi would not come so deep into the mountains at this time. These must be tengu.” He replied, “The reason we are cutting down these trees is none other than to use them as materials for the construction of the castle of our lord, Yūki Hideyasu. The castle is for the preservation and security of the entire province, and not for any personal gain.”

Hearing this, the yamabushi said, “If you are cutting these trees for such a purpose, then even if you have to cut down all the trees on this mountain, it must be done. I have nothing more to say to you.”

With that, they took their leave and climbed up the mountain. Ogasawara thought it was strange, and he followed them with his eyes as they disappeared into the shadows of the trees, but lost sight of them after a while. There were many people on the mountain as well, cutting timber, and they should have seen the yamabushi, but not even one of them did. Ogasawara’s son, Rihei II, was there with his father at that time, though he was a young child, and he later recounted that he had seen these yamabushi.