Today’s yokai is not the first zatō yokai we’ve seen on the blog, and it probably won’t be the last. I’ve written the translation for zatō down below as “blind man,” but there is a lot more to it that isn’t quite picked up by that translation.

In the Edo period, there was a strict caste system in place, and you could only perform the certain types of work that were allowed by your caste. It’s an unthinkable restriction by today’s standards, but back then it did more than just control the peasants; it also provided welfare for certain groups of citizens. For example, while there was no social security system back then, the government did establish guilds for the disabled so that certain types of work were reserved for them, reserving for them a way to make a living.

The zatō were one of these guild-like organizations. Only blind citizens were allowed to become zatō, and only zatō were allowed to perform certain types of work: anma, a traditional kind of massage, and playing the biwa, a lute-like instrument. This allowed blind people their own realm in which to prosper (No word on what blind people who weren’t interested in music, massage, or accounting did for a living.). The zatō guilds made enough money that they were able to become money lenders.

The zatō was a popular staple of Edo period art, especially ukiyoe, which depicted the dreamlike “floating world” of urban life, beauty, and pleasure. As a result, it’s no surprise that there are more than a couple zatō-based yokai stories. Blind Hōichi from the famous ghost story Miminashi Hōichi (“Hōichi the Earless”) is a good example.

Fans of Japanese film might know the character Zatōichi the blind swordsman. He is of course a swordsman but also a zatō. So there’s a lot more to this word than just “blind man,” but there’s not really an easy way to translate it. I prefer to leave the word as-is, because it has no English equivalent.

Ōzato

大座頭

おおざと

“giant zatō (blind man)”

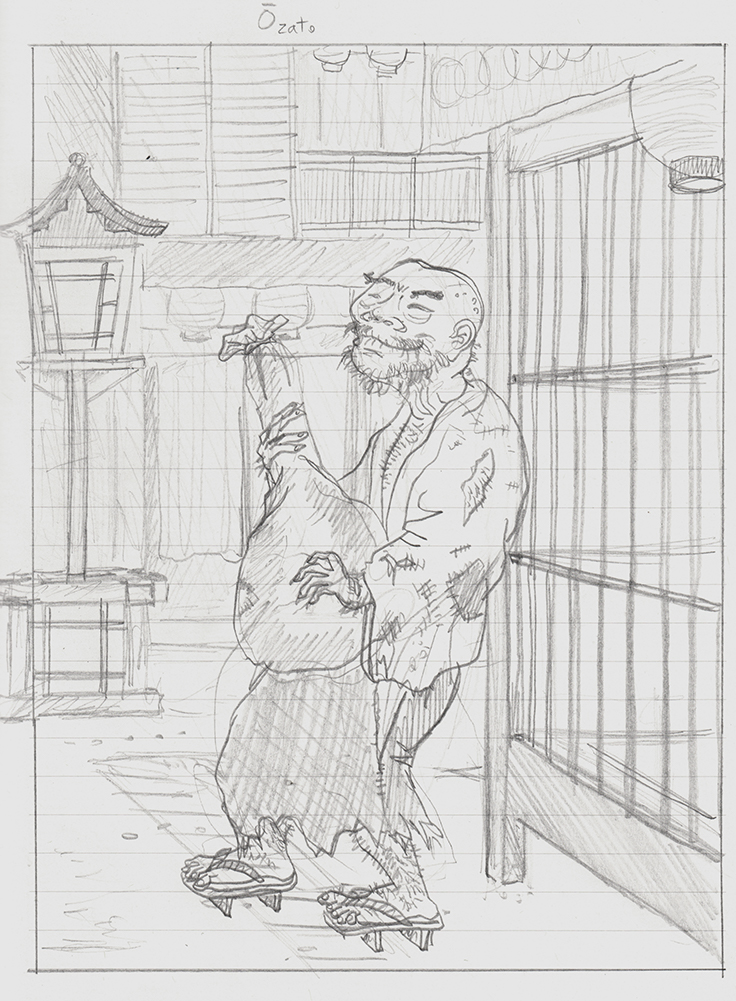

Toriyama Sekien’s Ōzatō

Ōzatō appear on windy, rainy nights, and usually loiter about the same areas night after night. They wear tattered, old hakama and geta. If you stop to ask them where they are going, they reply: “Always to the whorehouse, to play the shamisen!”

That’s all that Toriyama Sekien writes about them. It may not be much, but it does give you a bit of an idea of how Toriyama Sekien (and probably his readers) felt about certain zatō who loiters about late at night…

Some zatō were able to make lots of money from a few regular high-paying customers, and by profiting from moneylending and collection schemes. By manipulating guild fees, they could syphon funds away from the poorer guild members. It’s safe to say his opinion of these zatō was not very high either.

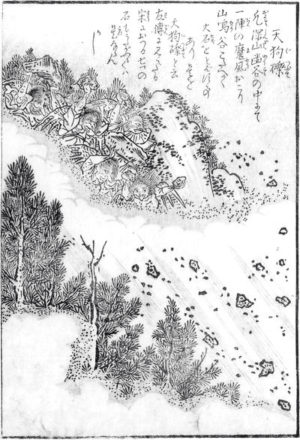

Sekien lived in a time of strong censorship, but he was about to hide his critiques of society in his yokai artwork. Among his yokai, there are a lot of -bōzu and -nyūdō (priests and monks) yokai, as well as a number of zatō yokai. He didn’t have a very high opinion of people who frequented red light districts either, judging by how many brothel monsters he slipped into his works.

Sekien especially did not look favorably on corruption among clergy. But can you blame him? Even today, who enjoys receiving solicitors, especially those who appear to be exploiting a disability to gain your sympathy? And corrupt priests are still just as infuriating today—just the other day we pulled into the gas station to fill up, and in front of us was an imported European luxury sports car with full leather interior. Out pops a monk wearing full robes, fills it up with high octane gas, and then ROARS down the street when he is done.

Many of Sekien’s yokai are not-so-subtle digs at these hypocritical aspects of society. Keep that in mind as we look at more of his monks and priests this week.