Hello everyone! Today is October 1st, and I am so happy because that means Halloween season is upon us! In the spirit of Halloween, as I do every year, I am painting one yokai every day: A-Yokai-A-Day for the month of October.

Just like other drawing projects (such as Inktober), I’m invite all readers to participate and share their own A-Yokai-A-Day images on social media using the hashtags #ayokaiaday and #ayokaiaday2018

Normally, I like to start A-Yokai-A-Day with some of the weirder or cuter yokai and gradually work towards the bloodier and scarier ones as we approach Halloween. However, you’ll notice that today’s yokai isn’t exactly what you’d call cute. The reason is that this guy comes out on the Autumn equinox, which was just over one week ago today. I wanted to share him early, since the equinox is still close.

So, let’s take a closer look at today’s yokai:

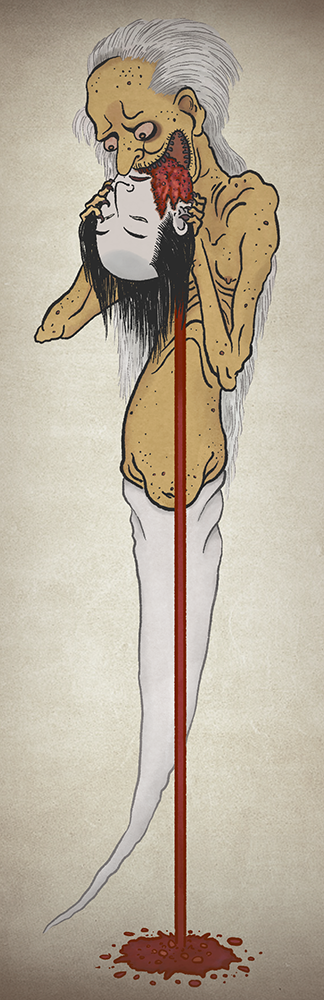

Kubi kajiri

Kubi kajiri

“head biter”

Kubi kajiri is a yokai that is found lurking around in graveyards on the Autumn equinox. As you may guess by his name, he is primarily hunting for heads to eat. They look very similar to typical Japanese ghosts: long, disheveled hair, discolored skin, sunken eyes, and a white burial kimono. Like Japanese ghosts, they have no legs.

When they find a corpse that has been freshly buried, they dig it up and begin eating the head, leaving a mess of blood and gore all over the ground.

The reason they look like ghosts is because they were developed from a painting (by Ippitsusai Bunchō) called “Ghost eating a man’s head.” At some point, the picture was copied and the name kubi kajiri was slapped onto it, and this character was born!

There are two different popular explanations for kubi kajiri’s origin. The first one says that they are created when a person dies and is buried without their head. Their corpse turns into a yōkai and begins to hunt for fresh heads in graveyards.

The other explanation is a little more gruesome. It says that kubi kajiri are created from the corpses of eldery people who have starved to death—particularly those who starved due to negligence and abuse. This is related to the idea of “ubasute” which occurred long ago when food was scarce. During famine, the elderly members of a family might be allowed to starve to death in order to relieve the burden on the younger members. When they were too weak to travel, the elderly might even be piggy-backed into the mountains by their children and left there to die. It’s so sad and cruel that there’s no wonder this is the original story for so many different kinds of yokai. In such cases, the kubi kajiri was only said to appear after their abuser died. Then they would appear beside the grave of their abuser, dig up the corpse, and devour its head.

Justice! (Maybe?)

Want more yokai? Visit yokai.com and check out my yokai encyclopedias on amazon.com! Still want more? You can sign up for my Patreon project to support my yokai work, get original yokai postcards and prints, and even make requests for which yokai I paint next!