This weekend I went to Nagoya to see the Yokai Mummy Exhibit at Parco Gallery. If you can get to Nagoya before this ends, I strongly recommend you go see it! It was pretty fantastic.

This exhibit is a preview event for a brand new yokai museum set to open next year in Miyoshi City, Hiroshima. The museum is going to be the new home of Yumoto Koichi’s yokai collection. Yumoto holds the largest collection of yokai in the world, and is a prolific yokai researcher with a few books published detailing the contents of his massive collection. Having a museum built for them is a pretty incredible thing, and this preview showcased some of the highlights of his collection; the mummies!

And unlike lots of art galleries, photos were allowed, so I am happy to share some of what I saw with you! You’ll have to forgive the poor quality of the photos. It was difficult to take shots without my own shadow getting in the way, so most of my pictures were taken at sharp angles. There are some glares and lots of perspective distortion, so you’ll have to use your imagination a bit.

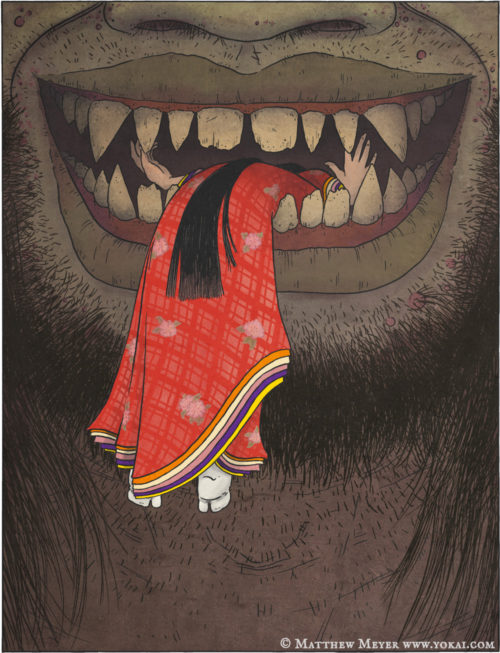

Part One: Paintings

Here I am peering at the first scroll: a hyakki yagyo emaki featuring tsukumogami cavorting in a night parade.

These are yokai you’ve probably seen countless times. They have been painted over and over in many different picture scrolls. Some have names, some don’t, but it’s fun to see the same characters appear over and over by different artists.

Next up is a picture scroll depicting a long story, with yokai interacting with humans among a lavish-looking samurai house.

Only parts of the scrolls were visible; they unfurl different sections of different days of the exhibit, so if you can go for multiple days you can catch even more of the stories!

Next up is a scroll with a number of famous yokai, including this old school nurikabe! I also liked this version of nurikabe more than Mizuki Shigeru’s version, which is what you mainly see nowadays.

This next character is heavily distorted because I took the photo at a sharp angle, but it’s a giant catfish! This was another scroll that had a number of large sea monsters on it.

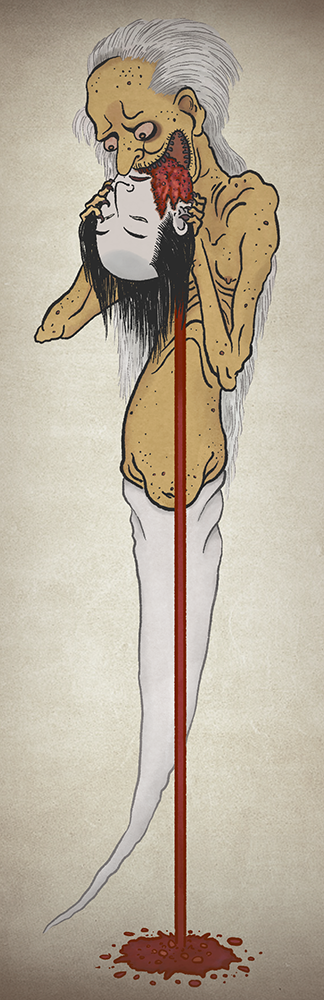

I know I’ve seen this ghost before! This is a copy of another painting.

An inugami and a rokurokubi, also copies from an earlier scroll.

The next one is a bizarre scroll worth mentioning. This scroll depicts a group of wisemen from China who developed a method of defeating yokai… by farting on them! Fart scrolls are surprisingly common among yokai paintings, and there are lots of images of people farting on kappa or other yokai to drive them off. I’m not sure how this particular scroll falls into the timeline of things, but the silliness of it is charming.

This is an Edo period book about a young man who goes kitsune hunting off in the mountains, and runs into yokai after yokai. How I would have loved to turn the pages and see the other parts of this book!

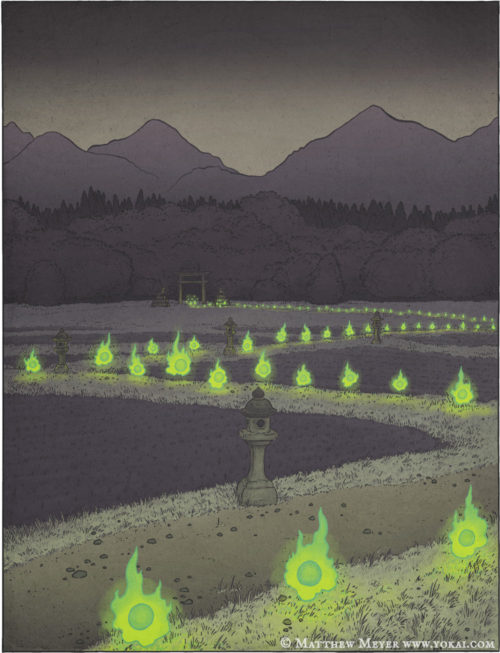

This scroll depicts a house full of yokai; you can see faces on the walls, and ghostly heads floating about.

These next few images were from a relatively modern (Showa Period) scroll, and I absolutely love them! In particular, chikusho (the skull with a skeletal deer’s body) has definitely become one of my new favorite yokai. This scroll was also unfurled over many days, so I wish I could come back and see the others! (Fortunately Yumoto Koichi’s books do display more details of this and his other pieces.)

Part Two: Prints

First up are two of the most famous yokai images ever: Hokusai’s prints of Oiwa and the sarayashiki ghost (aka Okiku). You can find better scans online than my photos, but seeing them in person is something else!

This is a copy of Inou mononoke roku, which I’ve posted about on here and yokai.com in the past. It’s a collection of pictures from the life on Inou Heitarou, a young boy from Miyoshi, Hiroshima who had a series of very bad nights as yokai repeatedly visited him. How I would love to read this whole book!

Next up is a series of prints framed all together. If you look closely you can see all kinds of yokai hidden in the pictures. Even the walls have eyes!

This story features a big tsuchigumo!

Below is a yokai-themed board game (sugoroku).

Here is a set of yokai karuta.

This is a newspaper article, believe it or not. It tells the story of a shop owner who was attacked by the ghost of the man who owned the shop before him. It looks like it would have been very fun to be a newspaper illustrator back then!

Part Three: Clothing

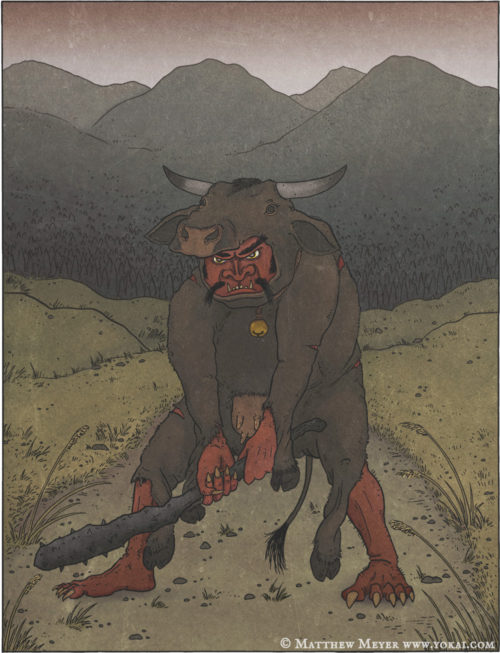

There were a couple of neat articles of clothing at the exhibit. This is a kimono and obi featuring Ibaraki doji, a famous oni.

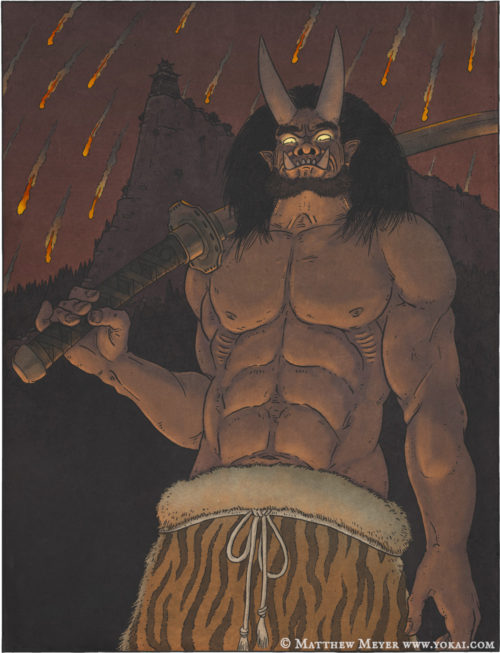

Below is a thick outer jacket with a nue on it. Nue were disaster beasts, associated with fire and lightning. So this jacket was actually worn by a fire brigade. It’s made of very thick and heavy cotton, like a judo uniform. The firefighters would soak it with water to protect themselves when running into the fire. Then they would turn it inside out when returning. It’s quite clever.

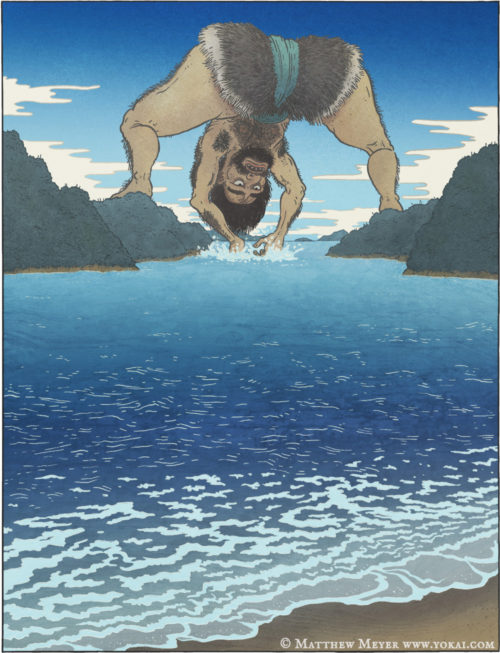

Part Four: Mummies!

This, of course, is the main event! The yokai mummies! In their day, these were toured around as sideshows, displayed in temples as curiosities, and even kept as charms.

First up we have a ningyo. The first page is a description of the creature and its story. Of all the man-made mummies, this one was by far the most realistic. Check out those teeth!

Next up is a creature that was billed as a “three headed dragon.” Three snake heads on an alligator. I guess it didn’t specify whose heads…

You’ve probably seen these images before. These famous kappa paintings are circulating around the internet. They diagram the kappa and suiko mummies presented below.

A kappa’s hand!! This reminds me of the old ghost story about the monkey’s paw.

This one here is a suiko.

This one here is a suiko.

Human for scale. I definitely picture suiko as much bigger in my mind! Isn’t that what people always say at sideshows?

Next up are a couple of raiju mummies. This illustration accompanied them:

There was also a karasu tengu mummy! This document describes it.

And now, the grand finale: the kudan! There were a number of posters advertising it from ages long past. I especially liked this one:

Human for scale. I’ve seen this guy on so many websites and in so many books. While there are other kudan mummies out there, this one is probably the most famous. He has a very serene look on his face. It’s not hard to see why people thought these were special or magical beasts.

Seeing these mummies really makes me long for a time I’ve never experienced. I’d love to visit that age of wonders, when science and fantasy were still at odds with one another, and sideshows like this traveled around the world. Although I suppose it’s not so different today. Instead of being scammed out of my money to see a “real mermaid,” I happily paid to see a fake one.

Anyway, it was an awesome exhibit. I am eagerly looking forward to the opening of Yumoto’s Yokai Museum in Miyoshi!