The Book of the Hakutaku has passed 1000% funding, and more stretch goals are being added. Today’s yokai, Shokuin, will be appearing in the book as one of the over 100 fully illustrated entries.

Shokuin

燭陰

しょくいん

“torch shadow”

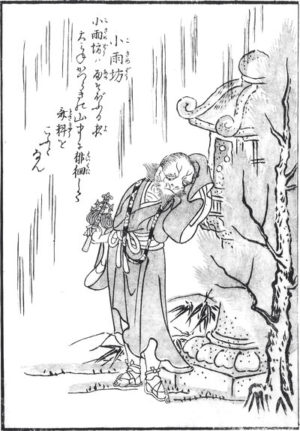

Shokuin as he appears in the Shan hai jing

Shokuin is an impressive beast. He originally comes from China, and was brought to Japan in the Sengaikyo (Chinese: Shanhaijing; “The Classics of the Mountains and Seas”), an encyclopedia of fantastical Chinese mythology. In China he is known as Zhuyin or Zhulong. (Shokuin is the Japanese pronunciation of the characters that make up Zhuyin.)

A lot of yokai were lifted from the Shanhaijing by authors like Toriyama Sekien—some of them more or less word for word, others undergoing a bit of a transformation and reinterpretation, depending on how much liberty the authors decided to take. Shokuin doesn’t undergo too much of a change from his original form.

Sekien describes Shokuin as a god who lives at the foot of Mount Shō, near the northern sea. He has the face of a human, and the body of a red dragon. His body is 1000 ri long (a ri is an ancient unit of measurement which varies quite a bit from age to age and place to place; and 1000 is a number which means “a whole lot,” so suffice it to say, Shokuin is big—at least a few thousand kilometers long).

Toriyama Sekien’s Shokuin

There’s a bit more information about him in the Shanhaijing which Sekien referenced. When Shokuin opens his eyes, it becomes daytime, and when he closes his eyes, it becomes night. When he breathes in it becomes summer, and when he breathes out it becomes winter. So not only is he big, but he is so big that he is responsible for the seasons and the days! He does not need to eat, drink, or breathe, but if he does breathe it causes huge storms.

Judging by his size and the unique side effects of his blinking and breathing altering the day/night and seasonal cycles, it seems that Shokuin was a personification of the sun, or at least a kind of solar or fire deity in ancient China. He appears in a number of other Chinese sources, but like all good mythology, there are contradictory “facts” about precisely where he lives and other details.

It has also been speculated that Shokuin is a deification of the aurora borealis. This makes sense when we consider that his home mountain is placed in the north sea, i.e. the Arctic circle. It’s also interesting to note that an ancient Chinese word for the aurora was “red spirit.” It’s easy to imagine the feelings an ancient explorer would have felt traveling far north and seeing the northern lights—a giant red line dancing back and forth across the sky. It’s only natural he might think it was a writhing red dragon thousands of kilometers long.