Try saying that three times fast!

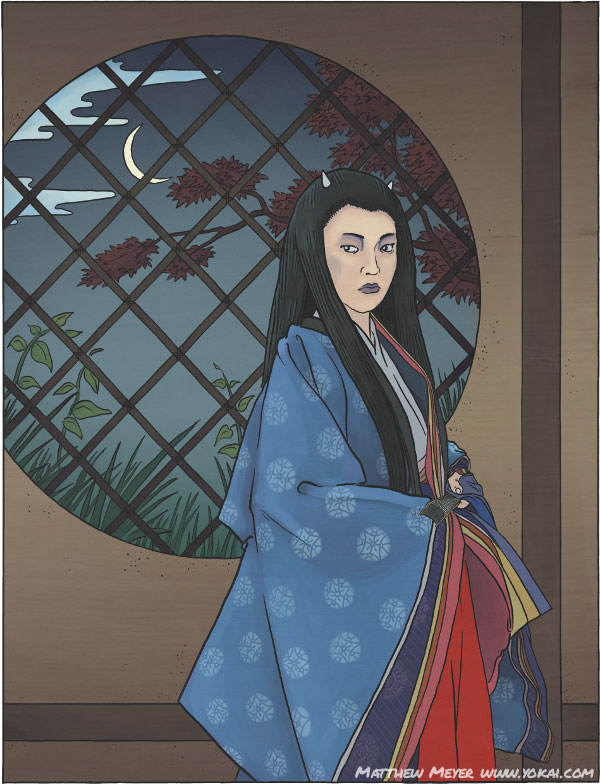

Rokujō no Miyasundokoro is an interesting name. From it we can tell a little bit about her. Those of you familiar with Kyoto will know that the town is divided into numbered neighborhoods (Ichijō, Nijō, Sanjō, Shijō, Gojō, Rokujō, Shichijō, Hachijō, Kujō, and Jūjō). You will probably recognize that her name means “6th street,” giving you an idea as to where she lived. The name Miyasundokoro starts with the kanji 御, which denotes a high rank; however, it is not the highest rank. In fact, her name (御息所) actually means “the place where the emperor sleeps.” It basically means “she who sleeps with the emperor.” In otherwords, she was one of many imperial concubines. Technically married to the emperor, and technically an aristocrat, she was not as high ranking as she might have wanted to be, and she would have been constantly competing with other wives for the favor of the court.

Lady Rokujō (I’ll call her that so you don’t have to keep trying to pronounce her name in your head as you read) is actually a character from Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji. This book hold an extremely important position in Japanese literature. It was the first novel ever written (in the world, not just in Japan), it is considered one of the greatest works of classical Japanese literature, and it was written by a woman. To get an understanding of it’s significance, it is considered to be as important to Japan and the Japanese language as The Canterbury Tales is to England and English.

Murasaki Shikibu is something of an adopted daughter of my “hometown” in Japan, Echizen city. Her father was appointed to a government position there, so she moved to Echizen from Kyoto along with him. Although she hated Echizen and wrote poems about how miserable she was an wanted to return home, the town loves her anyway. Actually, scholars think that some of the scenes in her works were inspired by her life in Fukui, so that makes her work of particular interest to me anyway.

Lady Rokujō’s chief rival in The Tale of Genji is a woman named Lady Aoi. In Japanese, her name is written Aoi no Ue. Ue means “up” and was actually a title denoting a certain societal position, just as Lady Rokujō’s name was. Japanese readers of The Tale of Genji can get this little bit of extra information about the characters, which is totally lost in translation when they are just written as “Lady Aoi” and “Lady Rokujō.” This is just one of the many complicated ways that English and Japanese differ from each other.

Anyway, before I digress too much about linguistics and Heian period court rankings, let’s get to today’s yokai:

click me! click me!