October is here, and you know what that means. A-Yokai-A-Day is upon us!

Every day of the month, in celebration of Halloween, I will be painting and posting yokai-themed work here on my blog. And I’d like to invite all yokai fans to participate along with me, by creating and sharing yokai art on social media using the hashtag #ayokaiaday.

If you enjoy A-Yokai-A-Day, please consider joining my Patreon. Support from patrons is what allows me to work on yokai full time. Without them, there is no way I could complete a project of this size in one month. My goal has always been to share yokai stories freely with the world, and I am so grateful to my patrons for their support in that effort.

This year for A-Yokai-A-Day, rather than sharing 31 unconnected yokai, I want to share with you a single, full story, translating one page per day and posting it along with an illustration and some discussion of the text. This book has 30 pages, which makes it perfect for sharing throughout the month in this manner.

The book I am sharing is called Hakoiri musume menya ningyo. It was published in 1791 by a famous publisher called Tsutaya Jūzaburō. The author is Santō Kyōden, who was famous for his sense of humor in writing. The illustrator is Kitao Masanobu. The first joke is right there, because Kitao Masanobu is actually a pen name for Santō Kyōden. He wrote and illustrated the book under two different names.

This is the story of a mermaid who falls in love with a human and marries him. You could call it the Japanese Little Mermaid, except that this story was published in 1791, nearly 50 years before Hans Christian Andersen published his famous tale. So in fact, maybe the popular fairy tale should actually be called the Danish Hakoiri Musume. And to be honest, I think this one is the better story of the two. It is full of multi-layered puns, it is outrageously silly, and it doesn’t have an awful ending that feels tacked on like Andersen’s story does. More than that, it offers a fascinating window into lives of people living in Edo in 1791.

The genre of this book is called kibyōshi. The word means “yellow cover,” which refers to the yellow paper used for the covers of these books (actually they were originally blue, but over time the dyes faded into yellow and this name stuck). Kibyōshi were the equivalent of dime novels or cheap pulp fiction of the 20th century. They were mass-produced, and written to appeal to a broad audience. They dealt with topics of the day, and in many ways serve as a snapshot or a time capsule of the pop culture from the year they were published. This book, for example, contains references to political events, popular music and theater, trending slang, and even celebrity name drops. When you think of literature of the 1790’s, you might think of Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Paine, or the Marquis de Sade—stuffy authors you were made to read in high school. But this book is so much more humorous and absurd than you’d expect from anything written in 1791.

Let’s talk about the title. Hakoiri musume menya ningyo is a bit of a mouthful, so I’ll break it down a bit. Hakoiri musume means “daughter in a box.” It’s a phrase that refers to girls who are overly sheltered by their parents and grow up knowing nothing of the world, as if they had been raised in a box. Menya is the name of a famous doll shop in Edo at the time period. Ningyo means “mermaid,” but is a homophone with ningyō meaning “doll.” Put it together and you can see that even the title is a pun with multiple meanings. It sounds like the doll shop Menya is selling dolls of girls in boxes. Or it sounds like they are selling mermaids in boxes. Or, it sounds like the story of a young mermaid who knows nothing of the world. Very clever, Kyōden!

The idea of a mermaid in a box carries one more connotation that is a little less obvious. It’s impossible to talk about Japanese mermaids without talking about misemono. Misemono were sideshows that were all the rage during the Edo period. And just like at Ripley’s shows, one of the most common attractions at misemono shows were mummified yōkai. Many of these mummies still survive today, and yokai fans may be familiar with the preserved kudan, tengu, and kappa mummies that I’ve shared on my blog before (here and here). Mermaids were one of the most common of these mummies, and yokai professor Yumoto Kōichi has said that the majority of the world’s mermaid mummies were produced here in Japan. I suppose it was easy enough to sew a monkey to a fish, put it behind a curtain in a dimly lit room, and charge a few coins for a flash glimpse of it. “Mermaid in a box” is a clear reference to these popular Edo period attractions, and misemono side shows are a recurring theme in the story itself.

Now that you know a bit about the background of the book, I need to write some acknowledgments before we dive in. I am able to write these posts thanks to universities and museums which preserved these treasures and making scans of them freely available online. The scan I referenced is part of Waseda University’s Kotenseki Sogo Database, and you can access the book yourself here. The Freer Gallery’s Pulverer Collection also hosts an online scan of a different printing of the book, which you can find here. I’m sure there are other copies available as well. We are so lucky to be living in a time where these books are preserved and made available in this way. Also, because books like these are very difficult to decipher (the script alone is nearly illegible, and the dialect is hard to digest as well—imagine reading handwritten Shakespeare), I referenced Tanahashi Masahiro’s Edo gesaku sōshi, which was invaluable to making sense of this work.

Now, with the introduction out of the way, I can share today’s illustration!

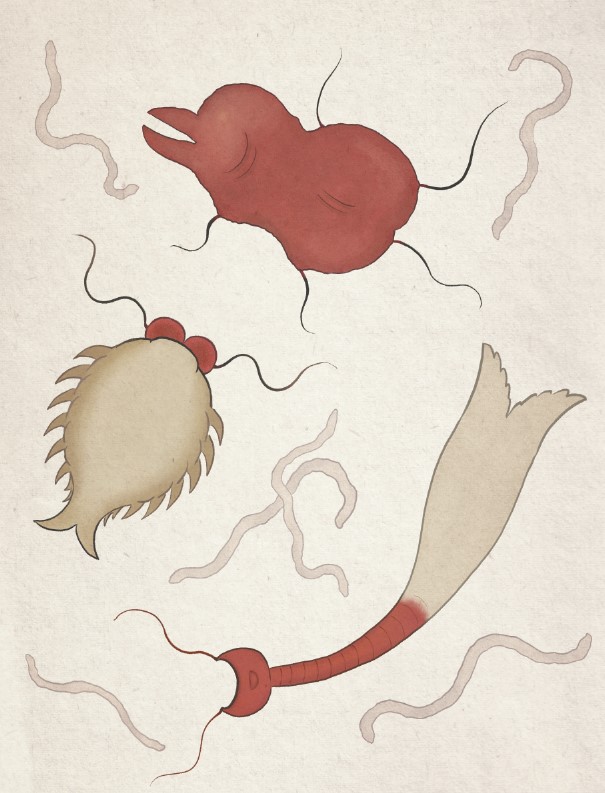

These are the main characters of our story. To the left, the titular mermaid, and to the right, Heiji, an elderly fisherman. Behind them is the title: Hakoiri musume menya ningyo.

Oh, and just so you’re aware, this is not a children’s story. It is funny, dirty, and meant for adults. It takes place in a red light district. It jokes about topics such as sex, sex work, coercion into sex work, the selling of women, child abandonment, human-on-fish bestiality, fish-cunnilingus, and I’m not censoring any of it. If you’re okay with all of that, then let’s get weird!