Tonight’s story is a sad one, with tragedy upon tragedy piling up. The yokai is called a daija, which literally means “giant snake.” However, when looking at Edo period illustrations of these stories, many times when they talk about giant snakes, the illustrators draw dragons—complete with beards, horns, spikes, even limbs. Yet other times, they draw actual snakes. Needless to say, this can be confusing. When is a snake just a snake and when is it a dragon? It’s hard to say, and folklore doesn’t seem to have a clear answer.

The Attachment of Shirai Sukesaburō of Gōshū’s Daughter, and How She Became a Daija

In the village of Tochū in Kita-gun, Gōshū, at a place called Ryūge Peak, there lived a rich farmer named Takahashi Shingorō. He had a five-year-old boy. Across the road from him was Shirai Sukesaburō, a less-wealthy farmer who had a three-year-old daughter. They were such close friends that they decided their children should someday be husband and wife, and they had them share a promissory cup of sake.

Not long after, when the boy was ten years old, Shingorō came down with a minor illness, and then died. After that, Shingorō’s family fortunes declined. Sukesaburō broke his promise and, when his daughter was fifteen years old, betrothed her to a wealthy farmer from a neighboring village.

The day of the wedding drew near. The daughter remembered that from a young age that she was betrothed to the boy in the house across the street, and she felt it was wrong to break that promise and marry someone solely based on declining wealth. She secretly sent her maidservant over to the boy across the street and called him over.

“As you know, you and I were promised to each other at a young age by our parents’ arrangement. But now I have been promised to another, and this vexes me tremendously. The wedding is to take place tonight. You must leave this place and go somewhere else, and take me with you,” she told him.

The boy replied, “I am deeply grateful for your offer, but I have been reduced to this poor state, and I absolutely do not begrudge you for that. You should marry into a good home.”

Hearing this, the girl said, “Then there is nothing else I can do.” She prepared to kill herself.

The boy was startled and held her back. “If you really feel that strongly about it, then I will accompany you anywhere,” he said. And so the two of them left together under the cover of night. However, they had made no arrangements with anyone who could help them, and so they rested in a certain place and were at a loss.

The girl said to him, “I cannot accept your offer to accompany me anywhere in the world. Let us throw ourselves into this pond, and let us meet again on a lotus leaf in the Pure Land in some distant future life.”

The boy agreed, and they joined hands as husband and wife, and became debris at the bottom of the pond.

However, somehow the boy got caught in a tree branch, and he could not sink. And just then, a passerby on the road saw him and pulled him out of the water, and he was saved. The boy believed that the reason he had unexpectedly gotten tangled in the branch was that his karma had not yet come to him. He shaved his head and became a monk, performed a funeral for the girl, and then returned home to his family.

Later, the boy’s mother traveled to Ishiyama Kannon to pray, and she saw a girl of fourteen or fifteen crying beside the Seta Bridge. She stopped to ask what was wrong.

The girl replied, “I am from a village north of here. My stepmother has been tormenting me in so many ways that I could not bear it any longer, so I came to throw myself from the bridge.”

The mother pitied her, and she told her, “Fortunately, I have a son. You can marry him.”

“Please allow me to do so!” she exclaimed.

The mother was overjoyed. She thought it was a match made by Kannon. She took the girl home, and her son and the girl were married. The son quickly forgot his sadness, and soon he and his wife were deeply in love like the hiyoku bird, and their love bore a son.

Before long, their son was three years old. One day, while her husband was away, the wife went into her room to take a nap. The boy entered his mother’s room, looked at his mother, and then cried and ran away. Then he came back in, looked at her, and cried and ran away again. He did this three times.

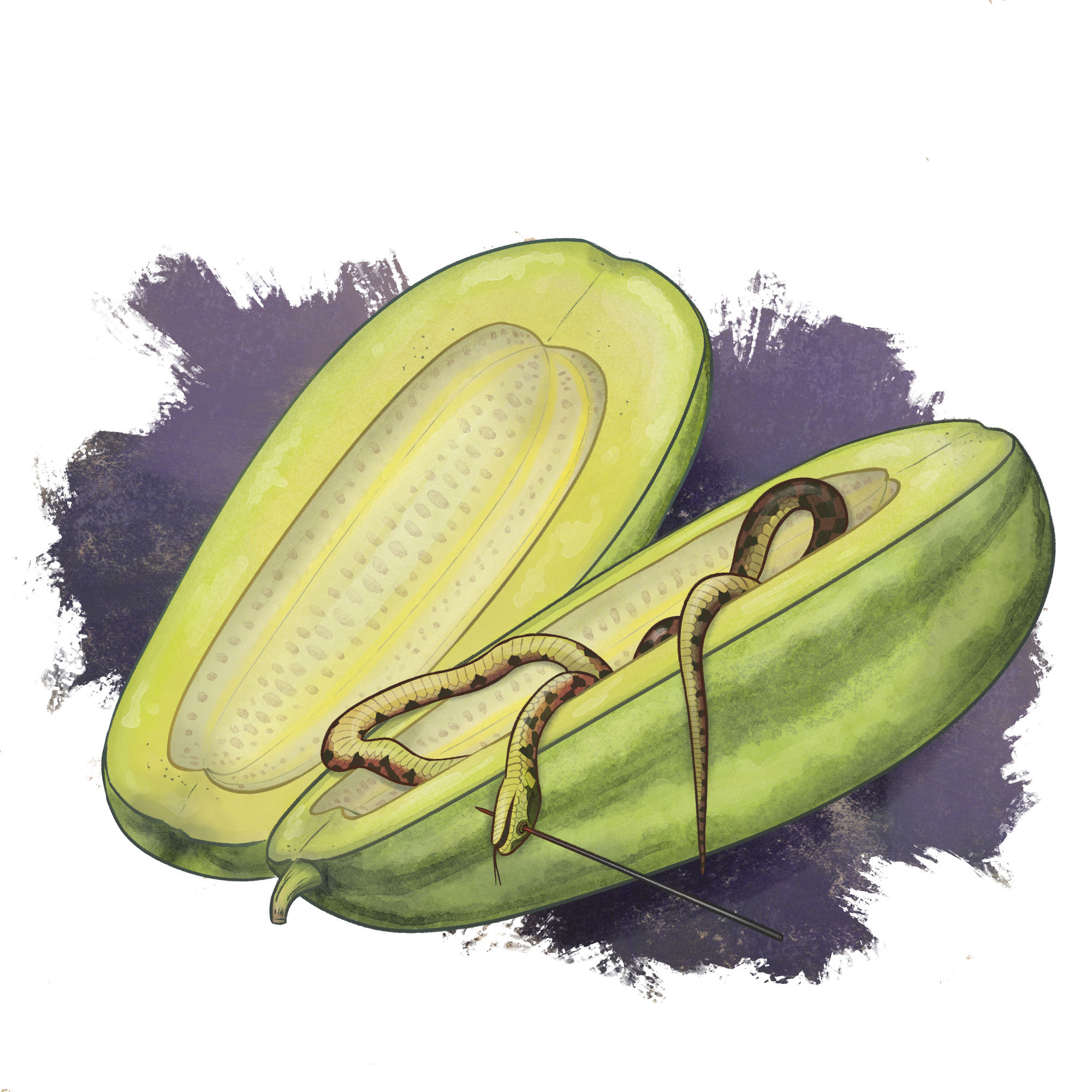

When the husband came home, he found this strange, and he entered the room to see what was going on. His wife had taken the form of a three meter long daija, and was fast asleep. The husband was horrified, and he called her name to wake her. The wife returned to her original form and looked at her husband.

“Well now, up until now I’ve been so careful not to show you my true form. I’m so embarrassed. I was the daughter of Sukesaburō. I was so attached to the idea of meeting you again that even death could not keep me from you. I changed back into a woman, and over the years, we have grown close to each other. Now it is over. I am sorry to leave you.” And with that, she vanished.

Afterwards, the boy incessantly asked for his mother. The husband, overcome with grief, took his son to the pond and said, “This boy longs for you so dearly, so just this once, please come and show yourself.”

Suddenly a woman appeared in the pond. She took the boy in her arms, suckled him at her breast for a short while, then bade her farewell and went back into the pond. After that, the boy yearned for his mother even more, and so once again they went together to the pond and called for her. This time she came in the form of a daija. She wiggled her red tongue, tried to swallow the boy, and then vanished. After that, the boy no longer missed his mother at all.

According to locals, the husband was so saddened by this that, afterwards, he and the child hurled themselves into the pond and died.