One of the reasons I began this project, and pretty much the main topic which has dominated this blog over the past 7 years, is bringing yokai to the English speaking world. When I first started talking about yokai on here, there were almost no books on yokai in English except for what had been writteb by Lafcadio Hearn, and other collections of Japanese folk tales.

Today, not even a decade later, that is very different. I have published two books. A number of other talented writers have published books on yokai and yurei, including Matt Alt and Zack Davisson, and of course Michael Dylan Foster who has the academic side very well covered. When you search Amazon for yokai books, you’ll find a huge number have come out in just the last few years. I have no idea what caused it to suddenly spring forth, but a huge surge in yokai popularity has come to the English-speaking world.

Now, on the heels of the handful of folks like myself working to share yokai with the world, Yokai Watch has hit US shores. For those who haven’t heard of it, Yokai Watch is a mega franchise in the vein of Pokemon which has taken Japan by storm. It has already surged past Pokemon in popularity, and that is no small thing to say.

And now the anime has just come to the US, airing on Disney just one week ago. The video game is set to be released soon, and no doubt a tidal wave of Yokai Watch goods will flood every market. Part of the reason for Yokai Watch’s success is that, like Pokemon, they are pushing every possible market: video games, tv, toys, and so on.

Although I haven’t watched the show and am not particularly interested in the game itself, I am very excited for this because it means yokai may be about to become a household word in North America. It means that a lot of young people are going to become aware of the idea of yokai, and there will probably be a lot of new fans of Japanese folklore made from this franchise. Even though many of Yokai Watch’s yokai are not quite “authentic” in that they were made up for the franchise, they still have roots in folklore, and will still drive people to learn more about their origins.

There has been some speculation that Yokai Watch might not take off in the US, because American kids are not familiar with the concept of yokai, and some concepts, like the idea of one of the main characters being the ghost of a cat who dies in the first episode might be too difficult for American kids to handle. Personally I find that a bit patronizing and an unfair underestimation of the intelligence of kids. But only time will tell.

Even if Yokai Watch doesn’t hit it big, I hope that at least a few kids and teens will be turned on to the world of yokai and folklore from this franchise!

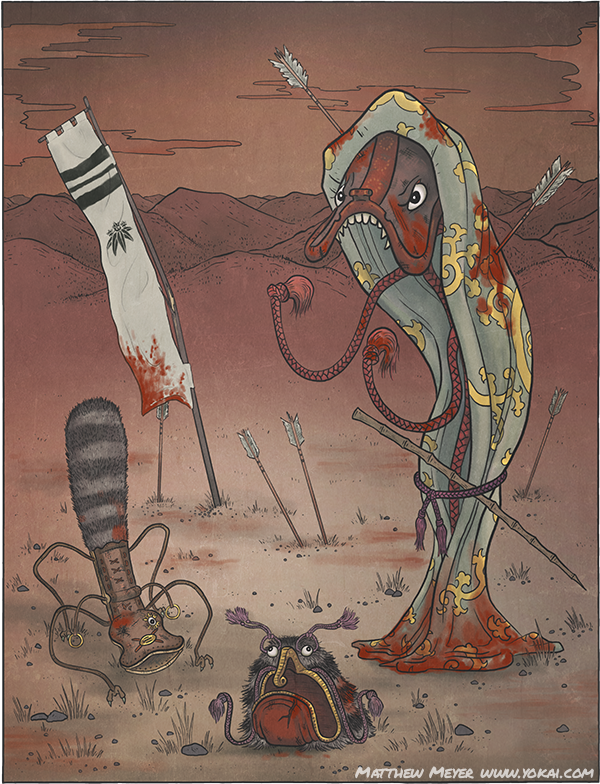

Anyway… today’s yokai is below! Kawa akago is a tricksy river imp who pulls people into the water. He’s quite a silly yokai, but also a dangerous one. You’ll find him in The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits. Click here to order it from amazon, and click below to view the entry on yokai.com!