Whenever I talk with yokai fans, I like to ask them what their favorite yokai is. And if I haven’t done an illustration of that yokai yet, I like to add it to my ever-growing to-do list. One yokai which keeps coming up as a fan favorite, no matter which country the person is from, is Tamamo no Mae. And for good reason too! She is beautiful, famous, powerful, dangerous, and well-known. So much so, in fact, that she is considered one of the three most evil yokai in Japan!

I have covered Tamamo no Mae on my blog before, many years ago, in the form of her ghost. However, when writing The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits, I decided that if the title includes “evil spirits,” I have to at the very least include the evilest spirits of them all—which is why Shuten douji, Emperor Sutoku, and Tamamo no Mae all made it into that book.

Actually, this is a blog post that I have been intending to write for a very long time—over a year now, in fact. It touches upon one of the most important parts of my work when writing these books: the research.

I take great care when researching my books. However, I don’t consider myself an academic, and my books and my blog are not scholarly works. For scholarly yokai books, I would recommend checking out the fantastic yokai works by Michael Dylan Foster. While I do include a general list of sources in my books and on yokai.com, I don’t have many direct citations in my text of where the information on each yokai comes from. There are a few reasons for this:

Firstly, I am writing for entertainment rather than research purposes, and I want to avoid falling into an overly academic writing style. My goal is to make English-language translations of yokai stories which are informative and accessible, while still really fun to read. So I try to keep the tone more like a storybook and less like a textbook.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, I reject the idea that there is a “correct” version of any particular yokai out there. So many myths and folk tales on the same subject differ from each other dramatically. Some even directly contradict one another. When this happens, how do you decide which one is “right?” It’s a difficult task, if not an impossible one, and it would feel dishonest if I were to just choose the one I like the best and label it as “authentic” while dismissing the others. My yokai stories are pulled from a number of sources, both academic and historical, but also “folk”—i.e. oral tradition and popular understanding. These “folk” sources include websites, bulletin boards and forums, Wikipedia, and other places where the source is either untrustworthy or completely lost due to repeated transmission without citation. How do you choose which one of this to favor? You can’t simply favor historical sources, because the nature of many yokai has changed over the centuries, and an oni from the 1100s is quite different from an oni in the 1800s. Which one is correct? Similarly, if you only go with proper academic sources over “folksy” sources, are you really getting the essence of “folklore?” I have heard professors on yokai and Japanese folklore give amazing lectures, going into the nuances and details of yokai, their symbolism, their connection with the changing culture of the time, and so on. I have also heard just-so-stories from people who have heard the legends passed down over time. And I have read blogs collecting these just-so-stories. Can you argue that only the papers written by academics who have spend decades studying yokai are more authentic than the blog by a guy who heard the story from a friend who heard the story from his grandmother who remembered it from her childhood? Well certainly the person who has studied for decades has earned a great deal of authority, but ignoring the free and wild aspects of a story would be to strip folklore of its “folk”-iness.

Therefore, when I write, I try to blend the historical with the contemporary understanding of yokai, and the academic accounts with the popular ones, to make the most interesting and accessible story for people to enjoy. When there are interesting contradictions, I try to include them. When there are different stories that come from different sources, I try to blend them to create a single narrative. Is this academic? No, not really. But I think it is the essence of what folklore is about. I think this is what people Lafcadio Hearn, Yanagita Kunio, et al were trying to do when they began collecting and adapting oral folk tales for audiences to read.

Okay, now that my little soapbox speech about writing folklore is done, I promise it has something important to do with today’s Tamamo no Mae entry! You see, Tamamo no Mae is not only the longest yokai entry I have in my book, she was by far the hardest entry to research and to write. The problem is her popularity. While many yokai are quite obscure, this actually can be a blessing: when there is only once source, there is only one thing I have to translate! When a yokai is super famous, then every author who has ever written about it has probably taken some liberties with the story—embellishing it here and there, adding bits and pieces to suit their political or religious motivations, and so on. When you have a yokai so famous as to be called one of “the top three evil yokai of Japan” you can bet you are going to find some difficult nuances!

When I began this blog post months ago, I was calling it “mapping the geneology of a yokai.” And that is basically what I was doing when researching and outlining my entry on Tamamo no Mae. I’m pretty sure that when her story originated, she was simply an evil kitsune who cursed the emperor. But later, as her story grew, and as it moved from oral tale to written one, bits and pieces began to get added. Now not only was she a nasty fox, she was actually a nine-tailed fox. And not just any nine-tailed fox, but a particular one; this one, which came from China!

I have no idea who the first person to connect Tamamo no Mae’s legend with Bao Si’s, but it was either a stroke of genius or a careless mistake. Connecting her with another well-known yokai makes her story a lot more appealing, but it adds a whole new canon to her geneology! Because now everything that is in Bao Si’s story is also part of Tamamo no Mae’s story, and wouldn’t you know—some storyteller, at some point in history, decided that Bao Si was actually the reincarnation (or reappearance) of Daji, a famous evil spirit (sometimes she’s a fox, sometimes she’s a dragon, sometimes somthing else…) from much-more-ancient China!

So my research of Tamamo no Mae then became research about Bao Si, and my research into Bao Si then became research into Daji. Each myth became more and more vague, and with each layer of myth I undercovered, the question of where do I stop haunted me even further. I mean, the legend of Tamamo no Mae really starts and ends with her Japanese incarnation, doesn’t it? All of the myth before must have just been tacked on, right?…

Well, I thought it was settled, I would just stick to her Japan-side history… until I came across an intersecting myth when I was researching my entries on Abe no Seimei and onmyoudou magic. You see, Abe no Seimei received his book of spells which became the basis for onmyoudou as a gift from an ambassador who went to Tang China from Japan, who in turn received it from a famous Chinese wizard. And this is the part where a young girl named Wakamo journeyed from China to Japan, and later became Tamamo no Mae. Seeing the names of these same characters come up while researching totally different yokai made me realize that perhaps I was too hasty in cutting Tamamo no Mae’s entries to just her Japanese debut. So I went back and delved further.

By now, nothing I was reading had anything to do with Japan. These were Japanese translations of Chinese chronicles, and didn’t contain many details about the connection between Daji and Bao Si. I didn’t want to include that in Tamamo no Mae’s story if it was too apocryphal or couldn’t find any connection at all… Even while there is no such thing as “true” when it comes to yokai, there has to be some kind of line to what we consider canon.

Finally, I found a Japanese legend that said after Daji was run out of Shang China, she fled to a land called Kosala where she married a demon king and together they feasted on babies and basically ran their country into the ground. Hmm….. okay, that was interesting, but what??? Surely there had to be some other mention of this character. The legend was far too wild to just end there. After weeks of searching in vain, I finally found a different legend that matched the story very closely: a fox spirit married the king of Magadha, convinced him to eat babies and kill priests, and was responsible for the downfall of the kingdom. The parallels were really strong, but where was the demon king, and was it Magadha or Kosala?

Eventually, I figured out that whoever wrote down these stories was probably as confused as I had become… Magadha and Kosala were both kingdoms in India, and their territories overlapped. The demon king had to be King Kalmashapada, who in Indian folklore is a rakshasa and who is known as Hanzoku in Japanese. Other Japanese legends referred to Hanzoku as having the legs of a tiger, and there was the connection! The confusion, I discovered, came from the fact that the Indian calendar measures time vastly different from the way the old Chinese calendar measures time, and when these stories were translated or interpreted by Japanese writers long, long ago, they either didn’t realize or didn’t adjust for these discrepancies! I felt like I had just solved the problem of time dilation on Star Trek or something.

So I figured out that Daji had ruined China and fled to India, ruined the country there, and then fled back to China to become Bao Si and ruin China again, after which she went to Japan and tried to ruin everything there, but she was ultimately killed. Even though none of these myths were connected to each other in their original forms, through the work of a handful of storytellers with a flair for the dramatic, each of these legendary people became part of the greater mosaic that is Tamamo no Mae. Whether they made these connections on purpose or out of carelessness, or to add an air of authenticity to their individual legends, this grand, era-spanning narrative was formed. It is a truly amazing example of folkloric gestalt.

The feeling after finishing weeks of research and making all of these connections was great. Thanks to Tamamo no Mae, I had studied more of Chinese and Indian ancient mythical history than I had ever imagine I would, even to the point of learning the strange ways that time was recorded in ancient Indian cultures. It was a really fun and educational experience. And after I had done all of that work, the question remained: how much of this do I put in the book?

My main goal was of course to chronicle her relation to Japanese folklore, so I didn’t want to over-focus on her bizarre and fairly apocryphal history, yet I had done all that work, and it was such a cool narrative that I didn’t want to leave it out. And the questions about folklore that I raised above come into play here as well. The “common” myths of Tamamo no Mae don’t have any awareness of these connections that were probably completely inadvertently made by past storytellers. I doubt there was any intention to ever say that Tamamo no Mae is the same character as the evil courtesan who convinced an Indian king to eat babies. And yet, the narrative works so well. Nobody I had ever spoken to was aware of much beyond Tamamo’s adventures in Japan. So which do you write? The obscure, probably accidental history that sounds awesome? Or the commonly believed history that more closely fits the definition of “folk” lore?

Ultimately I compromised and wrote up a version of her tale which includes her strange and fantastic history without going into much detail, and then focuses on her Japanese adventures. The Indian and Chinese parts of her tale don’t take anything away from her story, and if you don’t like them you can always ignore them as apocryphal and say that only the parts of her story that take place in Japan are “correct.” But like I said earlier, does “correct” have any real meaning when applied to folklore? My version is no more correct than anyone else’s. It’s just another variation of a story by someone who carries no more authority than anybody else who has a different variation. I think that is what makes something a folktale.

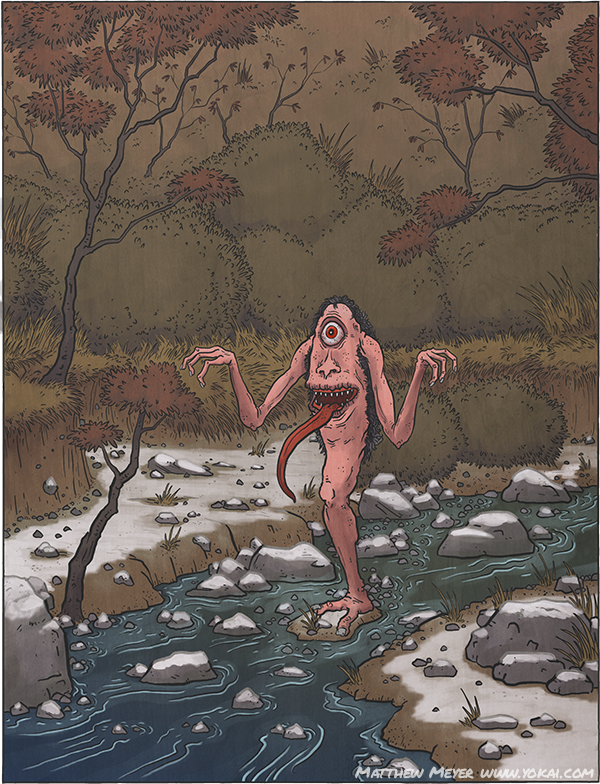

Tamamo no Mae – click the painting to view the story on yokai.com

Tamamo no Mae can can be found in my new book The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits. Order it now from Amazon.com.