Because folklore so often deals with scary things, I spend a lot of time going over monsters and curses and other things that are not so pleasant. In yesterday’s post we saw one of Okinawa’s most terrible curses, and I linked to a number of other magical spells that are pretty nasty in general. So today I thought I’d post something to remind us that magic is not always used for bad things.

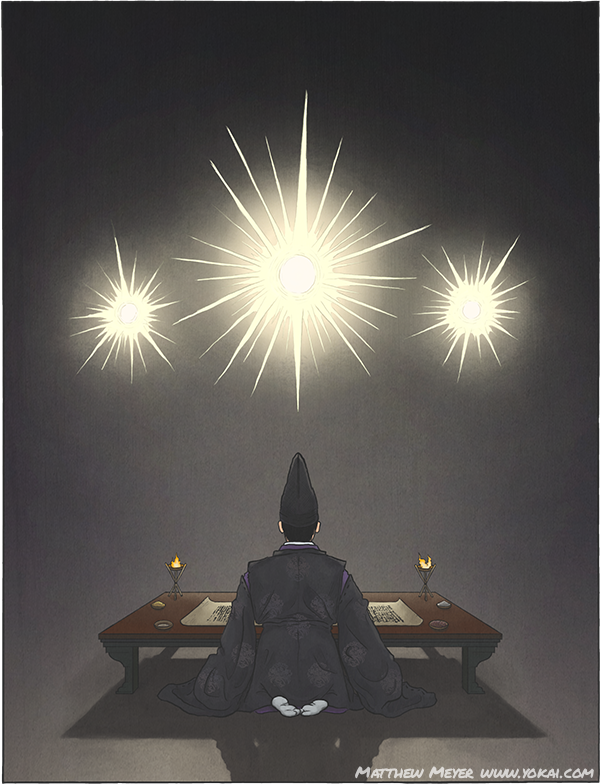

In fact, the majority of what omyoji did was not casting curses on other people, but actually trying to help people. Using fortune telling to divine when the lucky days were, discerning the unlucky directions and when the unlucky days were so that they could be avoided, discovering the causes of curses and providing protection from them, giving blessings for long life and health for the emperor, trying to cure the royals when they felt sick, and so on.

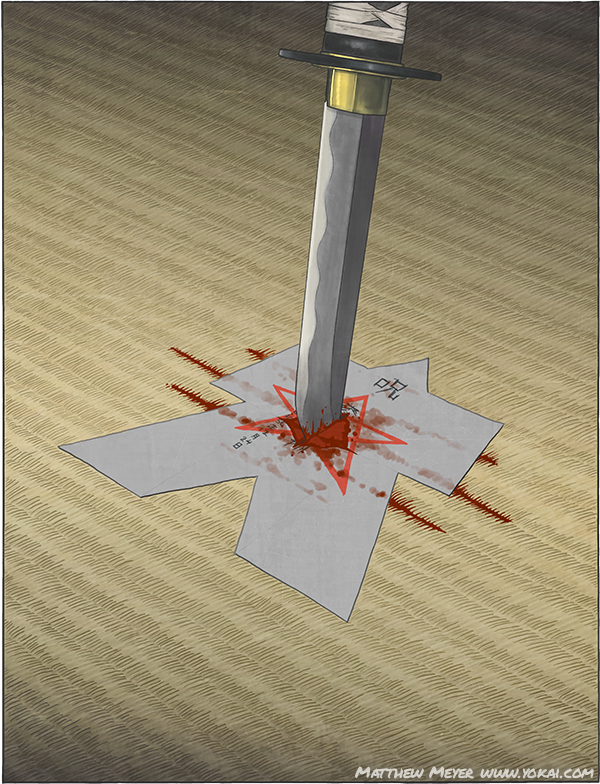

Of course, some of the more powerful sorcerers, the Abe clan for example, had protected family secrets that were passed down from generation to generation. One of these most important secrets was the ceremony of Lord Taizan, or the Taizan Fukun no Sai. This ceremony allowed him to return the dead to life.

It seems like something straight out of D&D; secret spellbooks passed down from generation to generation, wizards with demon-like familiars who do their bidding… I love it!

Click on the illustration to read on about this most powerful of holy spells: