Today’s yokai is a bit of a continuation of yesterday’s. When you combine the two yokai, you get a common word: chimimōryō (魑魅魍魎).

Chimimōryō, combining the words chimi and mōryō, is a common term which refers to all of the evil spirits of the rivers and mountains. It’s one of many catch all terms for Japanese monsters, along with mononoke, bakemono, obake, minori, yōkai, and so on. Today yokai is most commonly used to refer to the vast menagerie of spirits in Japanese folklore, but in the past, each of these other words have enjoyed varying levels of popularity.

Chances are if you speak to a Japanese person, they may not have heard of chimi or mōryō, but they have heard of chimimōryō. That’s because today this word is much more familiar as a catch-all phrase for evil spirits than as two specific yokai. Of course, it isn’t nearly as common as obake or yokai, which are the go-to words for supernatural creatures in Japan.

One more note that could be source of confusion about transliteration. You may notice that in some places on the web, yokai is spelled yōkai or even youkai. In fact, you may notice that a lot of yokai names are written with macrons like ō, hyphens, or other combinations. This can probably cause a lot of confusion, because in English we are used to every word having a single “correct” spelling. We even get into arguments over words like color/colour.

The nature of Japanese transliteration is responsible for a lot of confusion, particularly with yokai names. Technically, yōkai is the best way to write the word in English, but very few people know how to type those macrons on a keyboard, so they just write yokai. Technically, though, that ō is shorthand for ou, which would make youkai equally correct. Ou in Japanese is pronounced as a long o sound lasting two syllables. However, in English we tend to read ou as in the word “shout,” which changes the pronunciation considerably. Older transliteration systems have tried addressing this problem by writing a double o for such words (i.e. yookai) but you can see that really doesn’t fix the problem at all. These days, macrons are pretty when writing double vowels in Japanese, because it marks the fact that there is a double-letter there, while still remaining generally legible for English-readers. The pronunciation of yōkai is certainly easier to guess than youkai or yookai!

Also, there is an argument to be made that once a word has sufficiently entered English, it becomes part of the language rather than just a loan-word, and we don’t normally use macrons in English. (Some examples of such Japanese loan-words would be sushi, samurai, geisha, ninja, and shogun—which, like yōkai, should actually be written with a macron: shōgun!) Once foreign words have become sufficiently familiar to us, we tend to drop the marks (jalapeno, uber, el nino). The case could be made that yokai is becoming one of these words.

So in short, when you see mōryō, onryō, yōkai, hitotsume kozō, remember that all those ō‘s might also be written as ou, or even just o, but should be pronounced as a long o lasting for two syllables!

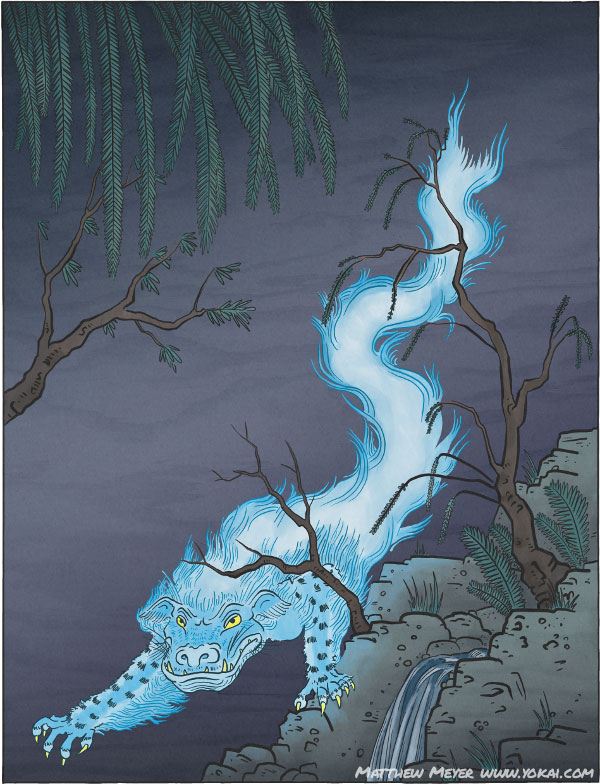

Now, on to today’s yōkai!