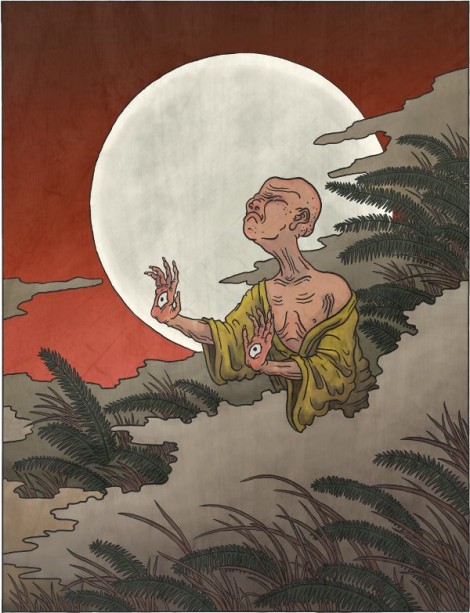

Today’s yokai is something you may recognize from the movie Pan’s Labyrinth. I love this yokai so much, not just because it’s creepy enough to give me the shivers, but also because it is such a perfect example of yokai master Toriyama Sekien’s art for irony and symbolism. This is a pretty long explanation, but I really think it is worth going in to. Enjoy!

Pan’s Labyrinth’s Pale Man: A Te-no-me?

Te-no-me (手の目, てのめ)

Te-no-me first appears in Toriyama Sekien’s Gazu Hyakki Yagyo. Unfortunately, this is another yokai for which Sekien didn’t even write a single sentence about — just an illustration — and so his original intent is lost to the mists of time. However, other older stories exist which describe monsters fitting te-no-me’s description, and perhaps it was these stories which Sekien based his yokai on.

Te-no-me takes the appearance of a zato, a blind man. Back in the Edo period, it would have been very difficult for a blind person to find work if not for the shogun-designated guilds. The guild system formed a sort of social security system, and it restricted certain professions to certain groups of people. The guild for blind people held a monopoly on the professions of massage, accupuncture, and biwa (lute) practice. Therefore zato is often synonymous with “blind masseur” or “blind biwa tutor.” A number of zato yokai exist, and you may have heard of the legend of Zatoichi, the blind swordsman? Yep, same zato.

Anyway, as I was saying, te-no-me takes the appearance of a zato, except for one crucial difference: his eyes are located on the palms of his hands instead of in his skull. In the Shokoku Hyakumonogatari (100 Stories from Various Countries, a yokai volume written in 1677), one story tells of such a creature, although the name te-no-me is not used. Instead, the word bakemono, or “monster,” is used. The title of that story is “The Story of the Man Who Had His Bones Sucked Out by a Monster.” Spoiler alert, amiright?

This story takes place in Shichi-jo, Kyoto, in a graveyard by the riverbank. A young man entered the graveyard, taunted by his friends to prove his courage by visiting a graveyard at night. Out of the darkness, an old man who appeared to be in his 80’s approached the young man. When the elderly figure got close enough to see in detail, the young man realized that it was actually a bakemono with eyeballs on the palms of his hands, and it was coming to get him!

The man ran as fast as he could to a nearby temple, and he begged the priest for sanctuary. The priest helped the man to hide inside of a long chest, and then hid from the monster himself.

Shortly afterwards, the bakemono entered the temple and hunted around for the young man. The noises got closer and closer to his hiding place, until they stopped right next to the chest he was hiding in. Then, there was a strange slurping sound, like the sound of a dog slurping and sucking on a dinner bone. A little while later, the slurping sound vanished, and all was quiet. Later, when the priest opened the chest to let the young man out, all that was left was the limp skin of the young man. His bones had been completely sucked out of his body.

I love that story… I don’t know why but it really chills my spine like few other yokai stories do!

A similar legend goes into a little more detail about where these yokai come from. In this story, a man is attacked by a bakemono with eyes on its palms in a field, and he flees to a nearby inn for shelter. He tells the innkeeper about the monster he saw, and the innkeeper replies that a few days ago, a blind man was attacked and robbed out in that field. As the man lay dying in the grass, he cried out, “If only I could have had once glace at their faces! My eyes do not see, but even if only I had eyes on the palms of my hands…” The old blind man’s resent-filled death is what caused him to be reborn as a yokai — with eyes on the palms of its hands just as he wished.

It doesn’t seem like this yokai became known as te-no-me until Toriyama Sekien dubbed it thusly in his encyclopedia. However, while te-no-me (literally, “eyes on hands”) seems like a painfully obvious name, Sekien had other reasons for attaching this name. They have to deal with Sekien’s unique sense of humor and his love of wordplay, and are rather difficult to translate into English, but let’s see what we can do:

It doesn’t seem like this yokai became known as te-no-me until Toriyama Sekien dubbed it thusly in his encyclopedia. However, while te-no-me (literally, “eyes on hands”) seems like a painfully obvious name, Sekien had other reasons for attaching this name. They have to deal with Sekien’s unique sense of humor and his love of wordplay, and are rather difficult to translate into English, but let’s see what we can do:

We have to start with a few idioms in Japanese. “Bake no kawa ga hageru” (lit. “transformed skin falls off” or “one’s disguise comes off”) is roughly equivalent to the English concept of the “wolf in sheep’s clothing” being revealed. That same word “hageru” can also be used to mean “to shaves one’s head;” and shaving one’s head can also be expressed by the idiom “bouzu ni naru,” (lit. “to become a priest,” as priests customarily shaved their heads). However, the phrase “bouzu ni naru,” is not actually used literally used to mean that someone will join the priesthood, but it is used when someone loses big time, at gambling or games or some other vice. The idea is “I lost so bad that I will shave my head and join the priesthood.” Now — hold that thought…

There is another phrase “te me o ageru” (lit. “raise the eye hands”) which means to expose someone’s trickery, particularly if they were cheating at something like gambling. If you are gambling and you catch someone at cheating (“te me o ageru“), they will be exposed for the cheater they are (“bake no kawa ga hageru“) and they will probably lose all of their money (“hageru,” “bouzu ni naru“) i.e. “become a priest.”

So what’s the connection? The obvious one is that “te me o ageru” is a play on words with the name te-no-me, with the yokai literally raising his eye hands. The rest of the joke lies in themes that run constant through much of Toriyama Sekien’s work; Sekien’s yokai books frequently mock the subjects he really hated, the big three of which were prostitution, gambling, and religion. This yokai doesn’t have anything to do with prostitution, but the subtle references to those idioms relating to losing at gambling and become a priest would not be lost on his clever readers. Amazing how just the simple name of a yokai can evoke so much!

tsuki (hanafuda)

Sekien’s illustration of te-no-me also includes subtle jokes: we see this yokai wandering through the grass under the moon. This is evocative of hanafuda cards, specifically the card for moon and grass. In hanafuda, moon, or tsuki, can also be written bouzu, (which as you may have noticed above, also means “priest”). And hanafuda is, of course, a card game, which is another poke at gambling.

Sekien managed to squeeze one last joke into his illustration: the grass in the hanafuda moon card is specifically pampass grass, which in Japanese is susuki. This evokes another idiom: “yuurei no shoutai mitari, kare obana,” literally “seeing the ghost’s true form, dry pampass grass.” The idea behind this idiom is that when you see something horrifying like a ghost, you may be scared, but in reality it is only something as simple as dry grass blowing in the wind. Your mind is just playing tricks on you.

Toriyama Sekien was truly a brilliant man!

If you liked this yokai, don’t forget to become a supporter of my Kickster project! Only 22 days to go!