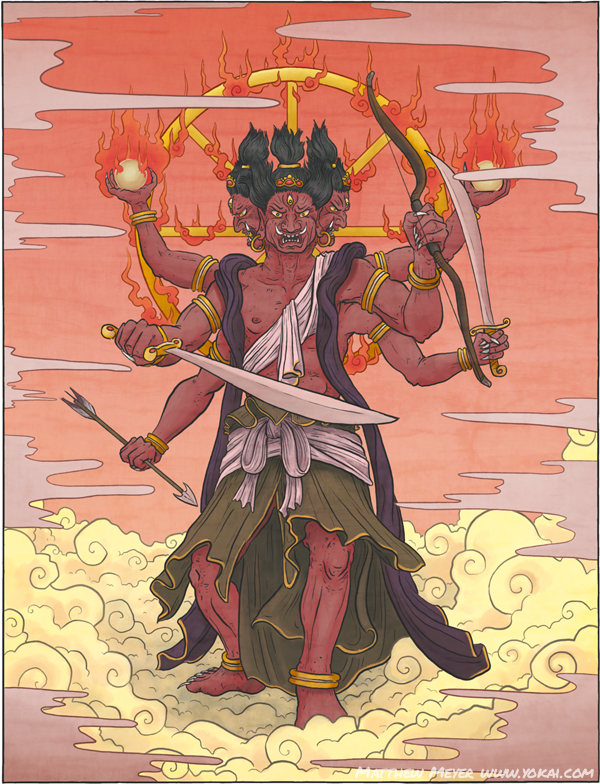

Today’s yokai also comes to us from Indian folklore, brought to Japan with the coming of Buddhism, just as the ashuras were. In fact, you could almost consider this yokai to be the opposite of an ashura.

In Buddhism, there are 6 “realms” of rebirth: heaven, ashura/asura, humans, animals, gaki (or hungry ghosts), and hell. When you die, you will be reincarnated in one of these realms.

Where you are rebord depends on the karma you earn during your life. The ranking changes from tradition to tradition—some put humans above ashura—but this is one commonly accepted ranking of the favorability of the realms. Some of these realms are familiar to us; the gods in heaven and the suffering denizens of hell are no stranger to us, even though the Buddhist versions of them differ slightly from Western customs. (I did a writeup on hell a while back which can also be found The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits.) The realm of humans and animals are pretty easy to understand, of course. And we learned about ashura yesterday. Today, I’ll tell you a bit about gaki. But first…

Of all of these realms, heaven is of course the most pleasant. Gods have nearly unlimited power and live lives of sheer pleasure. They live for uncountable aeons and enjoy so much. However, the downside to being a god is that eventually, when your time is up, you are almost guaranteed to go waaaay down to hell for the next life. Gods have very little concept of justice, you see. They get whatever they want whenever they want. Life goes so well for them that they earn an awful lot of bad karma, which comes back to bite them in the butt.

Ashura are similar to gods. They are super powerful, and have subjects to rule over. They are kind of like demi-gods. But, like gods, they are not able to concentrate on the better things in life. They are constantly jealous of the power that gods have which they don’t. They are always fighting and destroying and overcome with feelings of wrath and jealousy. So when they die, they tend to go to hell as well.

Hell, of course, is the worst place of all to be. Unlike in Western cosmology, Buddhist hell is not eternal. It may last for trillions of years… but you will get out eventually, after you have burned off all your bad karma. Then you get a respin at the wheel of reincarnation for a chance at something a little milder.

The realm of animals isn’t so bad… you get a fairly decent life. However, you are constantly at the mercy of the weather, of other animals, of lack of food and water… you don’t get to enjoy much, but you don’t suffer like those in hell either. Ultimately, though, the animal realm is not the best place for reincarnation.

The human realm is considered by Buddhists to be the best place to be reborn. It’s not the most pleasurable, of course; heaven is far nicer than the human realm. However, the human realm has just the right amount of pleasure and pain that humans can have a shot at controlling their karma. The gods have too much pleasure, the denizens of hell have too much pain, ashura are too violent, animals are too dumb… It is believed that only in the human realm can one succeed at finally producing no karma, and thus no longer being reborn; i.e. ascending into Buddhahood.

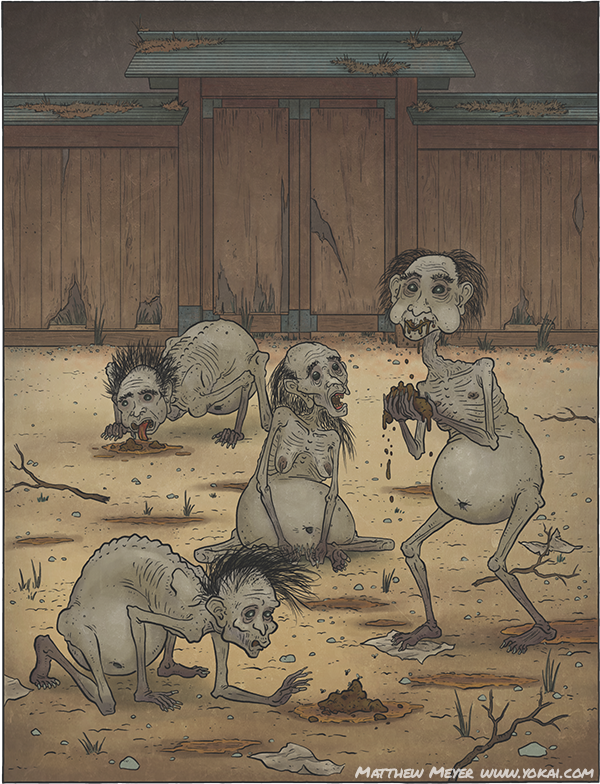

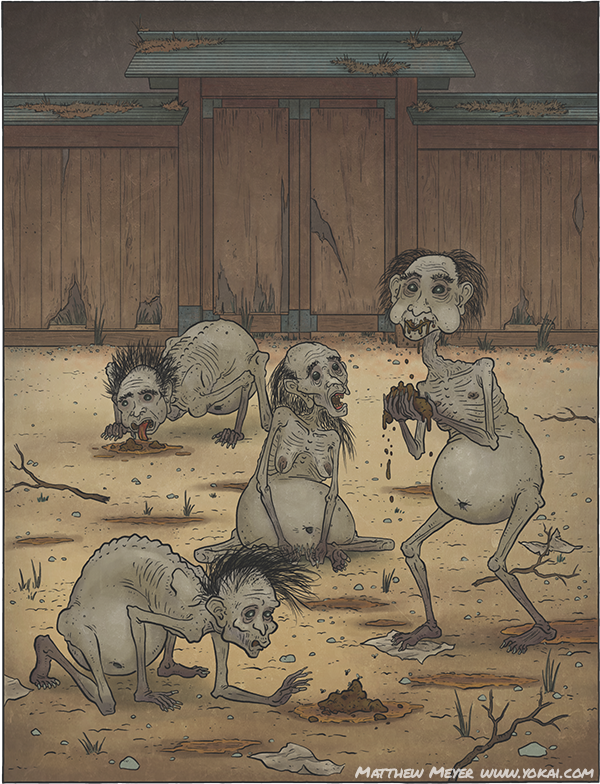

Lastly, there is the realm of gaki. This is commonly known in English as the realm of hungry ghosts, or by its Sankrit term, preta. These are lost spirits that didn’t have enough karma to be reborn into the animal realm, but were not bad enough to go to hell. It’s not a pleasant place. They are constantly hungry, and forced to eat excrement, blood, dirt… anything, as they try to sate their hunger. However, they can never be sated, and always suffer. A gaki is not tortured like a hell-being is, but a gaki is always suffering from the most basic life instincts, and lives its entire life in misery. Obviously, also not a good place to learn how to become a Buddha.

One question that often comes up is where do yokai fit in in all of this? Are they gaki or ashura, or something else?

Yokai are not Buddhist, and so there is no official ruling on what exactly they are. I’m sure some priests would say they exist somewhere in these realms. Certainly yurei are strongly connected with Buddhism in Japan… but yokai? Not so much. In fact, most folklorists say that yokai don’t fit in at all. They don’t live in a realm of reincarnation. Yokai live in ikai, the “otherworld,” and do not reincarnate, or maybe don’t even die. I haven’t really heard any Buddhist doctrine on yokai, except for one example:

Did you guess tengu? If so, good job! Tengu have long been considered the main enemies of Buddhism in Japan. Tengu are one kind of yokai which there is a direct path to becoming: a human that is so wicked, so evil, that they do not even deserve hell can become a tengu. They are reborn in Tengu-do, or the realm of tengu—a place outside of the wheel of reincarnation from which there is no escape. Tengu never get a chance at becoming a Buddha or being reborn in a better world. They are stuck there forever, as a yokai, forever apart from happiness and barred from enlightenment.

So even while the gaki seems like an awful existence, remember that it could be worse. You could be a tengu!

Gaki – http://yokai.com/gaki/

Click on those miserable gaki to visit yokai.com and read all about them! And pick up your copy of The Hour of Meeting Evil Spirits to read about gaki, ashura, the underworld and hell!